Bb Clarinet Multiphonics and Extended Techniques

Microtone

An interval smaller than a semitone, the smallest denoted unit of intervallic distance within the western classical music framework. Typically achieved with cross fingerings or altering the effective tube length in which the air/energy has to travel.

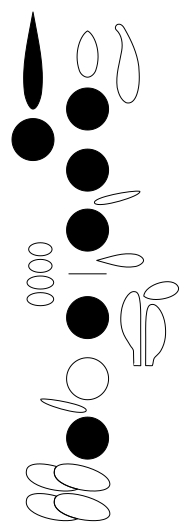

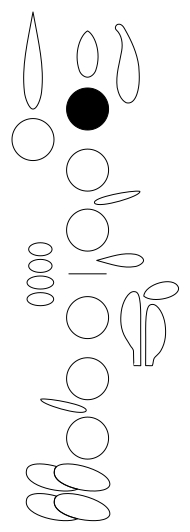

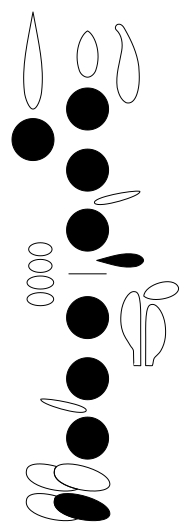

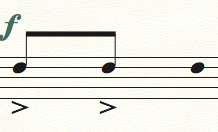

Microtone 1

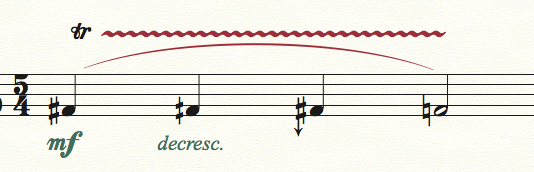

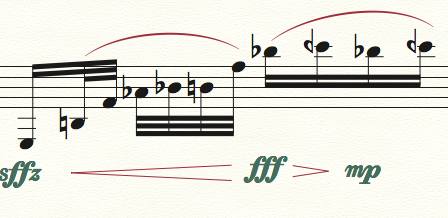

Eric Mandat - Tricolor Capers, Movement I

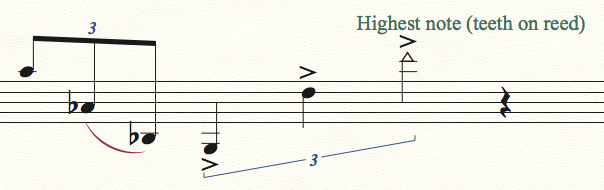

This example, in Movement I, oscillates between F6 (half flat) and E6, in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

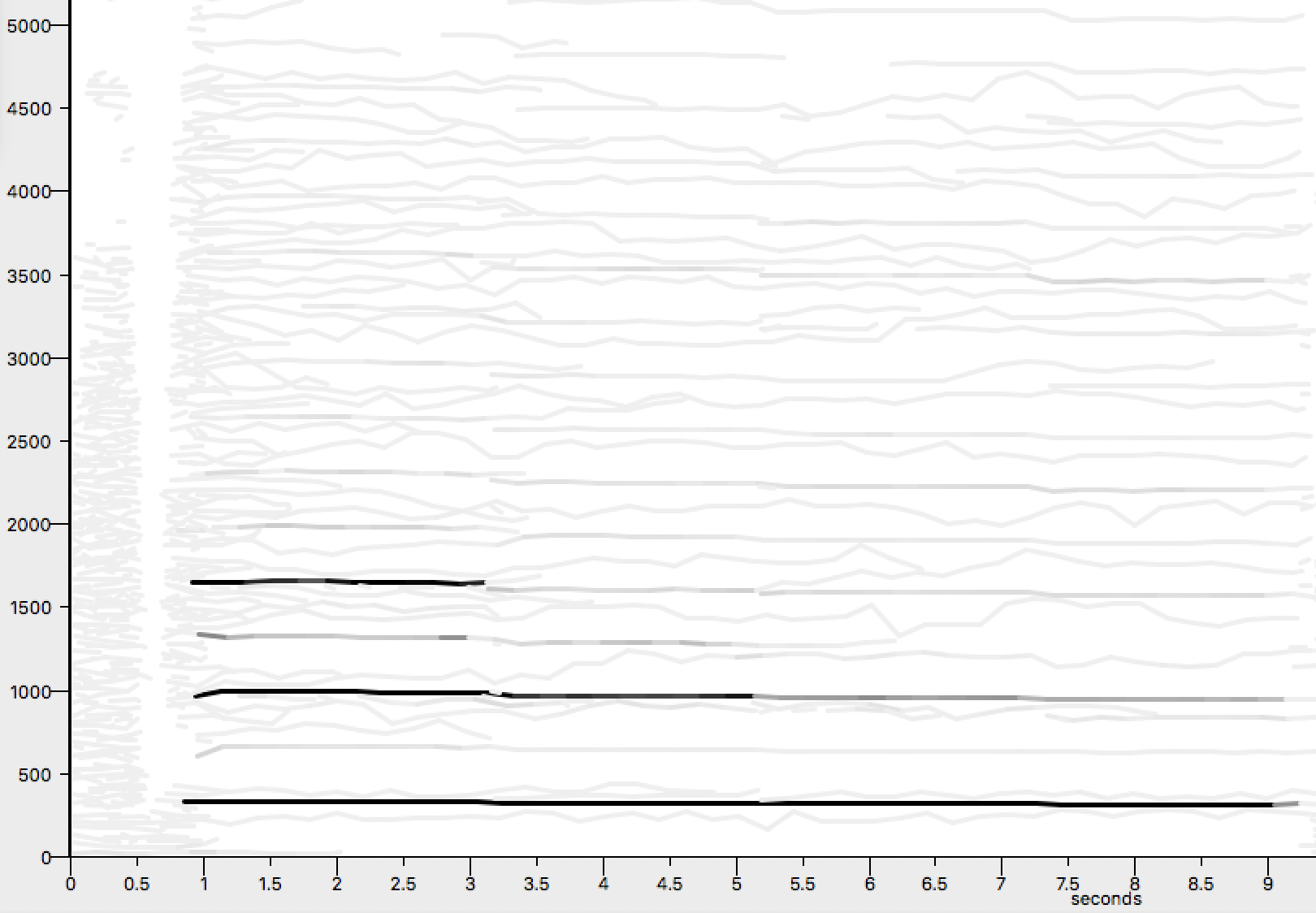

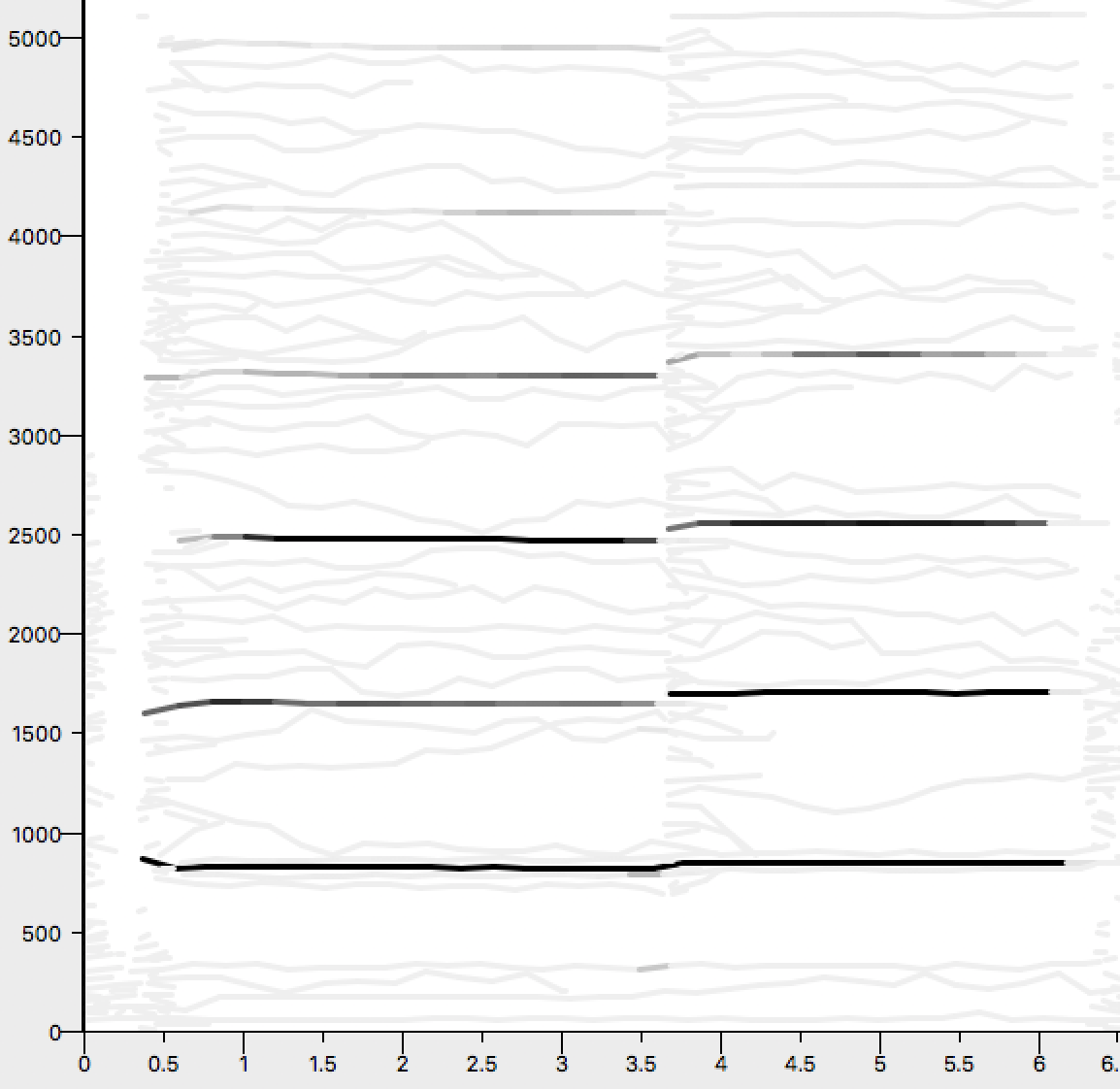

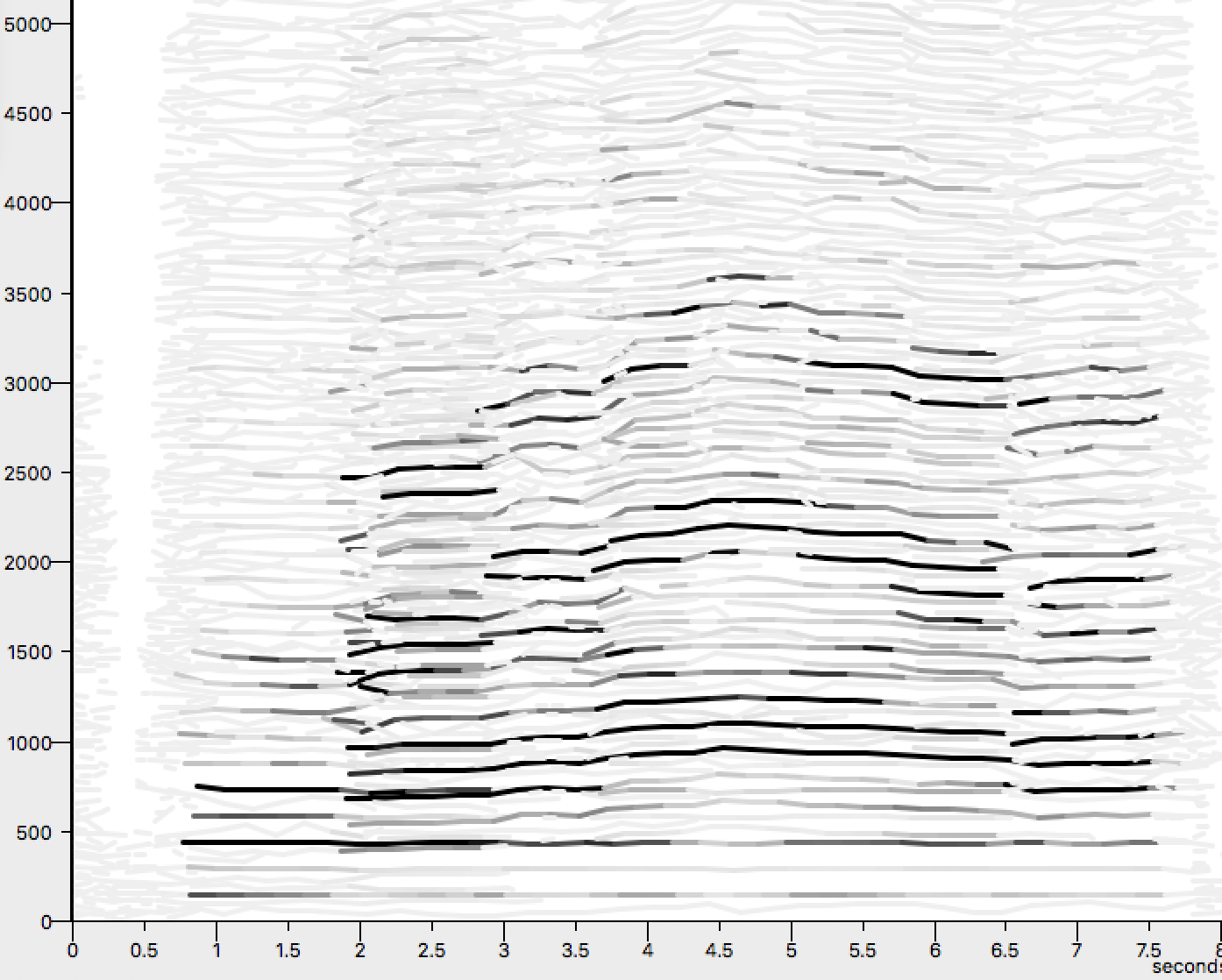

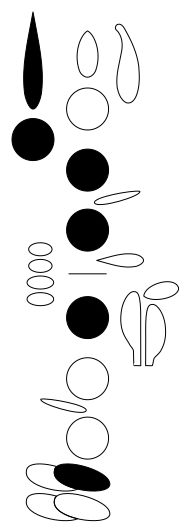

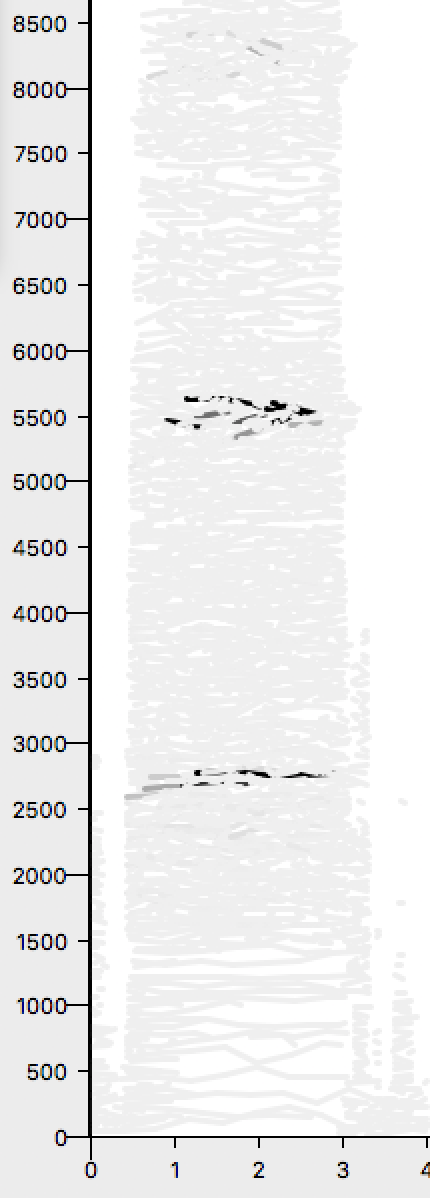

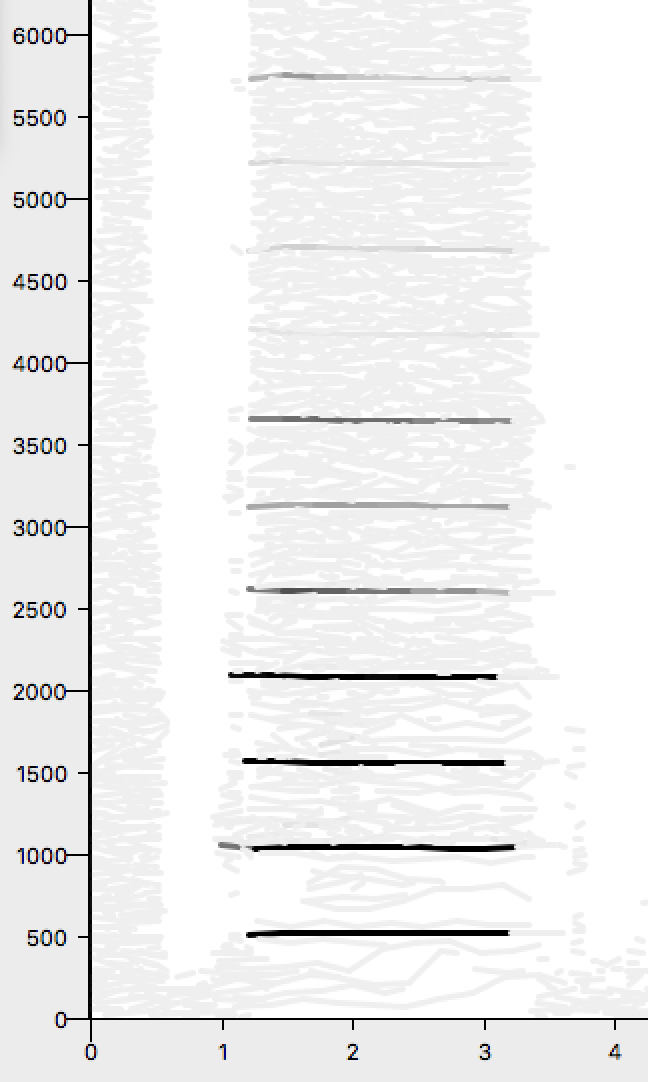

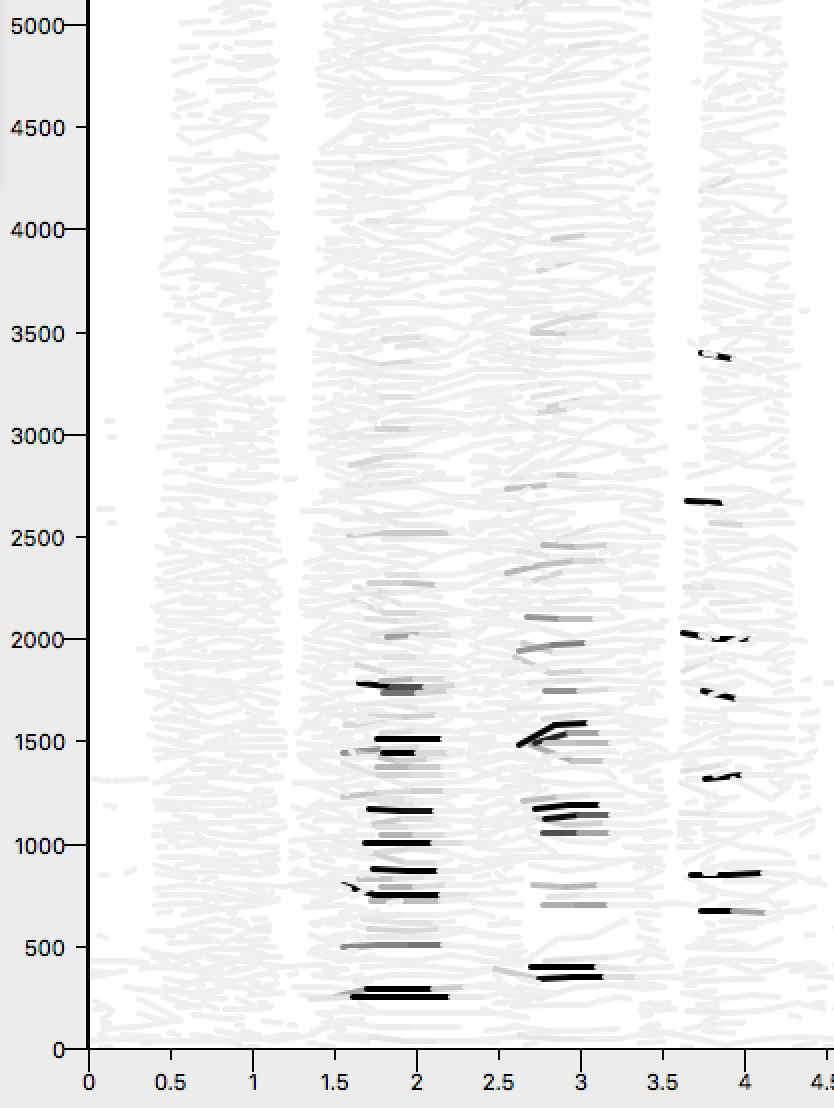

This is a prime example of how microtones are achieved through cross fingerings and altering the effective tube length. Switching from |1 2 on the right hand to |1 3 creates a tuning disparity between the two sounds. Some of the air or energy now has to travel a different distance as tone hole 3 on the right hand is closed. This raises the pitch and gives the rough notation of Fb (half). The spear graph (measuring pitch in hertz on the y axis and duration in seconds on the x axis) visually confirms the slight alteration of the fundamental and its consequent partials above, moving in parallel whole integer motion regarding the harmonic/overtone series of the instrument. This microtone can be easily reproduced as the notation shows the fingering chart alterations as the only mechanical difference to produce the slight change in pitch.

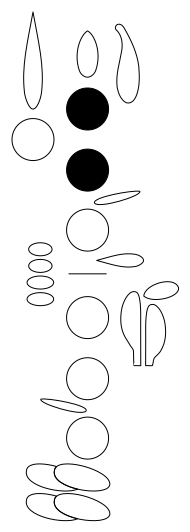

Microtone 2

Eric Mandat - Tricolor Capers, Movement II

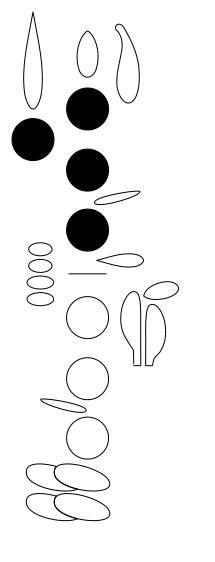

This example, in Movement II, continues to close tone holes on the upper joint and notates its tuning relation within the same note. Splitting the distance of F#4 to F4 to four equidistant notes, in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

This example splits the movement from F# to F, typically only in two equidistant notes with the presence of semitones, into four equidistant notes. Closing tone holes further down the instrument is changing the effective tube length where the air/energy has to travel. Each iteration adds another fingering down the instrument, bringing the original pitch lower. As with many of these technique examples, the notation doesn’t accurately define the intervallic relationships, but instead a general description and direction of the pitch alteration. The spear graph shows the fundamental frequency staying relatively constant, with the partials above moving slightly downward with each fingering change. This microtone is a bit more difficult to reproduce as the notation isn’t accurately noting the intervallic relationships.

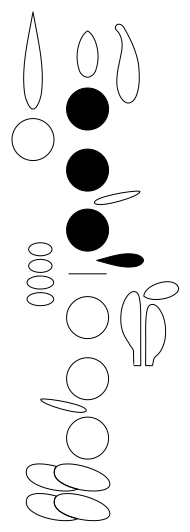

Microtone 3

Ronald Caravan - Excursions, Fragment 6

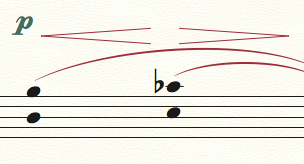

This example, in Fragment 6, oscillates between Bb5 and Cb6 (half flat), in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

Similar to Microtone one, this is a prime example in relating a microphone to a reference pitch that is acoustically designed and sound for the instrument. The movement from the Bb to the Cb (half) allows parallel movement of the fundamental frequency and its respective partials. This microtone can be easily reproduced as the notation shows the fingering chart alterations as the only mechanical difference to produce the slight change in pitch.

Multiphonic

“The acoustical phenomenon for producing two or more simultaneous pitches” or sonorities at the same time. (Rehfeldt, New Directions for Clarinet). Typically achieved through changing/altering vibration modes that are created by oral cavity or vocal fold manipulations along the vocal tract, known as voicing.

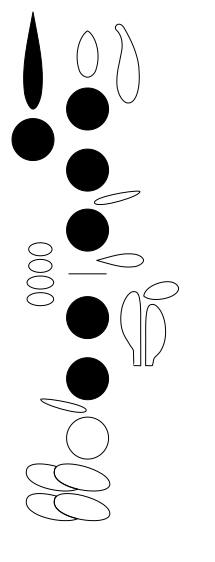

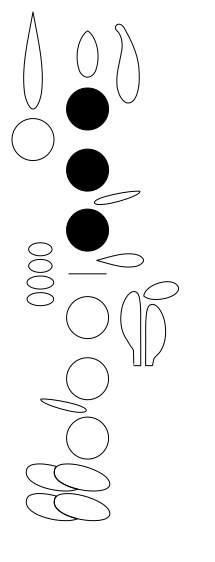

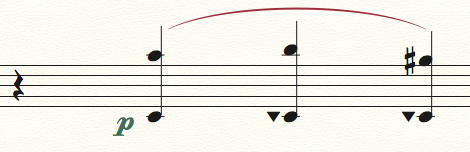

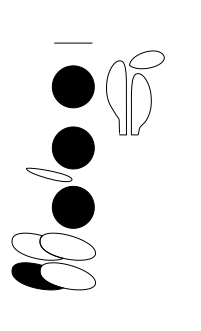

Multiphonic 1

Ronald Caravan - Excursions, Fragment 13

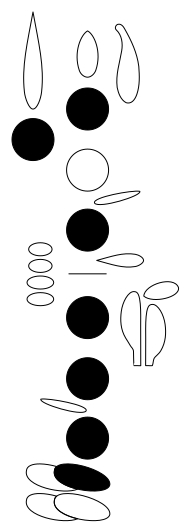

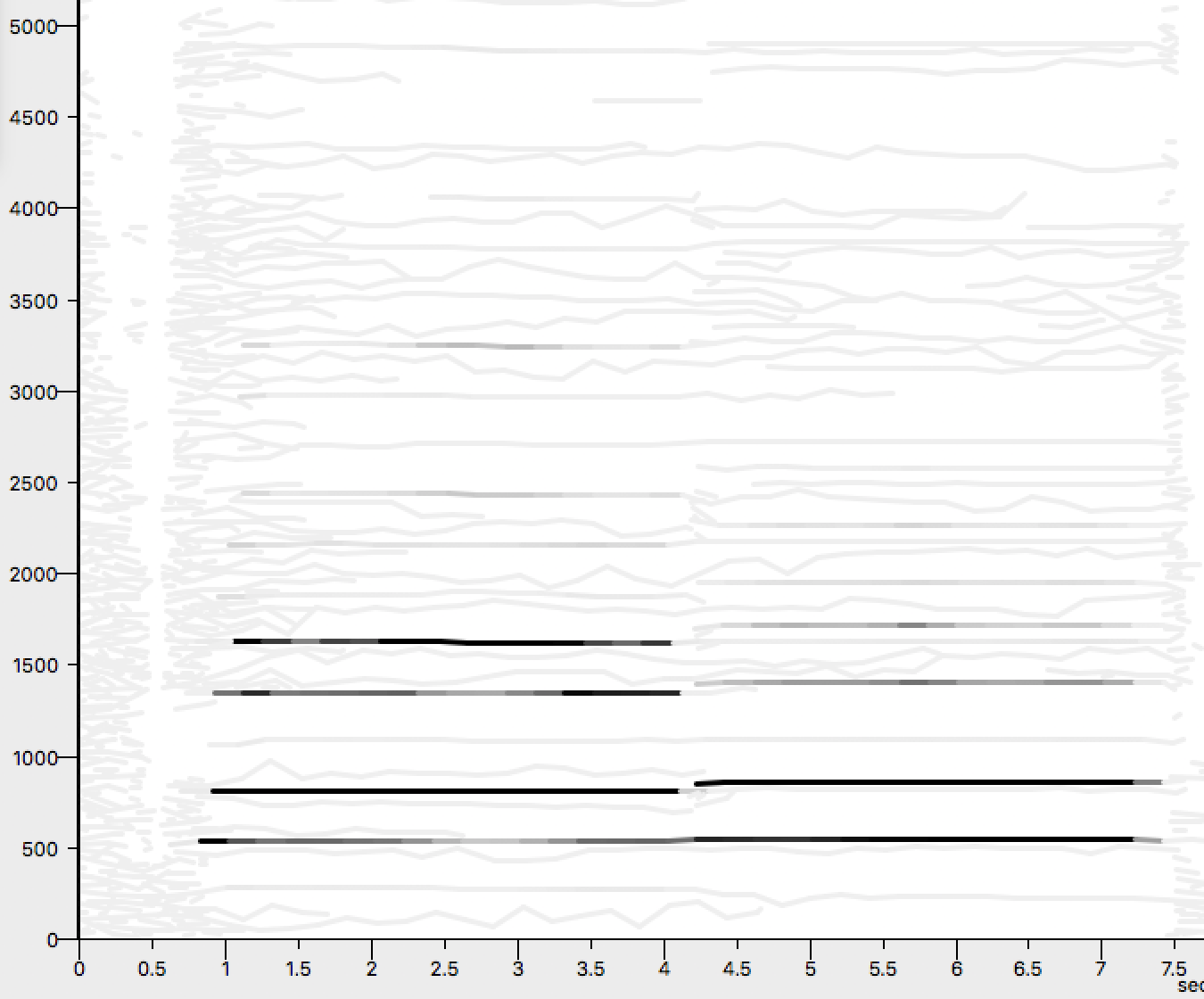

This example, in Fragment 13, has three sonorities sounding at the same time: D4, Gb5, and C6, in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

This is a prime example of how microtones are achieved through cross fingerings and altering the effective tube length. Switching from |1 2 on the right hand to |1 3 creates a tuning disparity between the two sounds. Some of the air or energy now has to travel a different distance as tone hole 3 on the right hand is closed. This raises the pitch and gives the rough notation of Fb (half). The spear graph (measuring pitch in hertz on the y axis and duration in seconds on the x axis) visually confirms the slight alteration of the fundamental and its consequent partials above, moving in parallel whole integer motion regarding the harmonic/overtone series of the instrument. This microtone can be easily reproduced as the notation shows the fingering chart alterations as the only mechanical difference to produce the slight change in pitch.

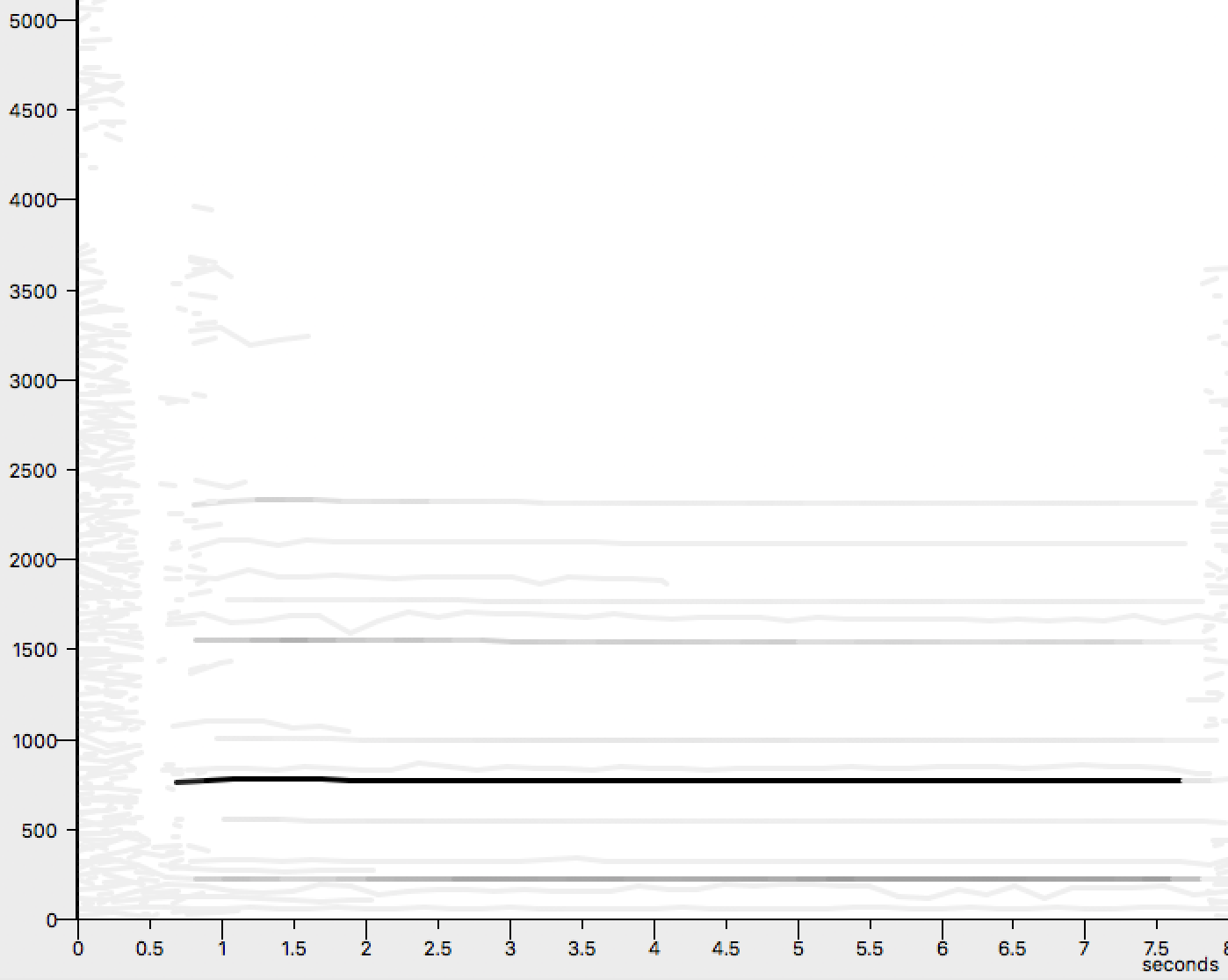

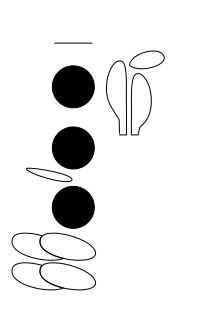

Multiphonic 2

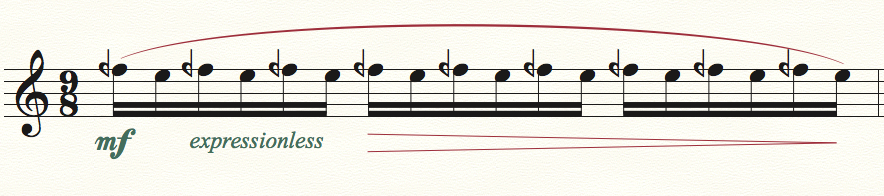

William O. Smith - Epigrams, Movement II

This example, in Movement II, has two sonorities sounding at the same time: C4 and A5, in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

This multiphonic has two sounding sonorities at the same time. This multiphonic is relatively easy to produce as there is only a slight tongue manipulation from how you currently voice the A6. The middle/back of my tongue raises up a bit more to achieve a clear dynamic for both sonorities. Allowing less air/energy into the system means that both notes may not be well and equally supported with each other. In this case, further oral manipulation can occur.

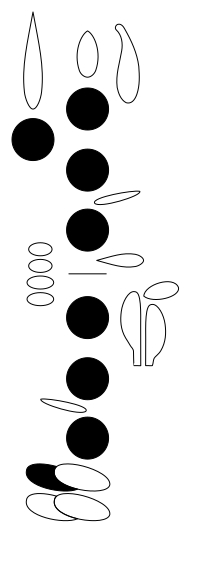

Multiphonic 3

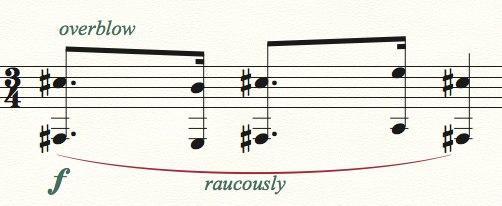

Eric Mandat - Tricolor Capers, Movement III

This example, in Movement III, has two sonorities sounding at the same time, created through overblowing to the next partial: F#3 and C#4, in written Bb clarinet pitch.

Conclusion

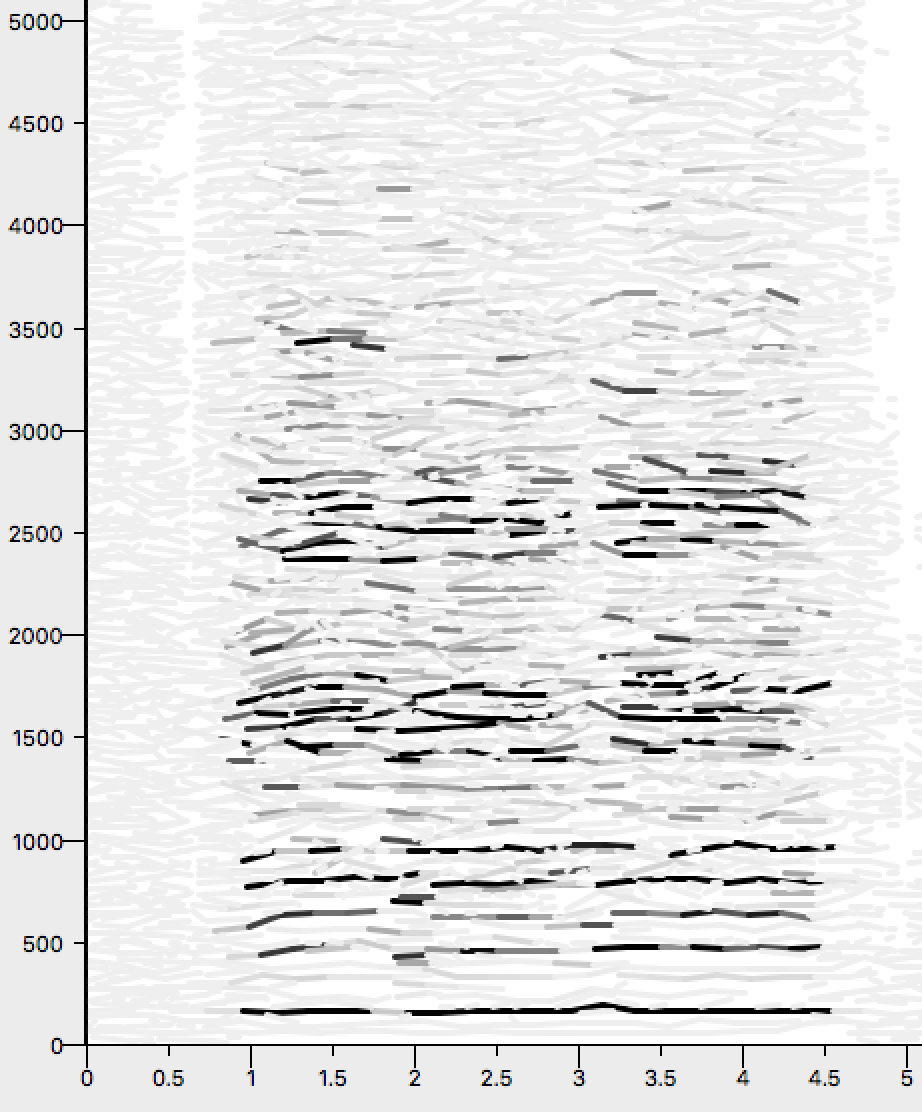

This overblowing technique, allowing more energy into the system than needed (in addition to an oral manipulation of moving your tongue up and forward), produces the next available partial in the harmonic/overtone series. The spear graph shows the heavy presence of the upper partials in this excerpt. This technique can be a bit difficult to produce due to the voicing manipulations.

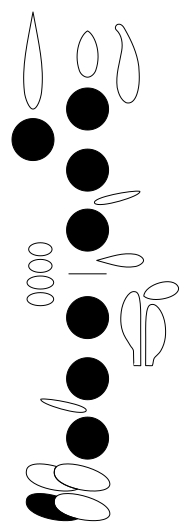

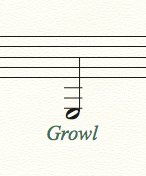

Growling

Disruption of the sound through singing or oral cavity or vocal fold manipulations along the vocal tract.

General Technique

Conclusion

This growling technique allows you to excite the upper partials with control of oral manipulation. The spear graph shows the fundamental frequency staying constant. Through only voicing manipulations (no change in fingering or outer embouchure), you can excite different vibrational modes and allow different partials to sound. This technique is relatively difficult to reproduce as the production of sound takes a great deal of control regarding tongue manipulation.

Flutter Tongue

Disruption of the sound through tongue manipulation of air along in the oral cavity.

General Technique

Conclusion

This technique disrupts the passage of air flow from the oral cavity into the instrument. The spear graph shows one main difference. For flutter tonguing in the middle chalumeau register, higher partials disappear compared to the regular sounding frequencies. The tongue acts as a filter in this case, clearing the higher partials. This technique can be relatively easy or difficult.

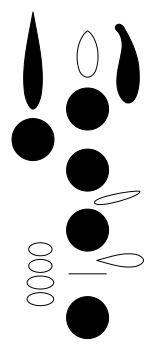

Teeth on Reed

Different application of pressure on the face of the reed.

General Technique

Conclusion

This technique disrupts the passage of air flow from the oral cavity into the instrument. The spear graph shows one main difference. For flutter tonguing in the middle chalumeau register, higher partials disappear compared to the regular sounding frequencies. The tongue acts as a filter in this case, clearing the higher partials. This technique can be relatively easy or difficult.

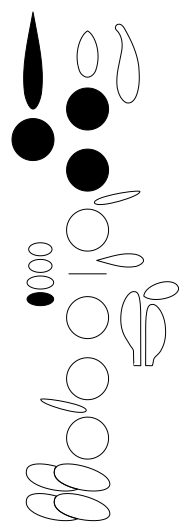

Respective Joints

These next three techniques show a manipulation of the effective tube length. For the upper joint, there aren’t many large disparities in pitch when compared to sounds created with the upper joint on the full instrument. The lower joint is a prime example of how changing the effective tube length causes alterations in pitch and intervallic relationships between notes.

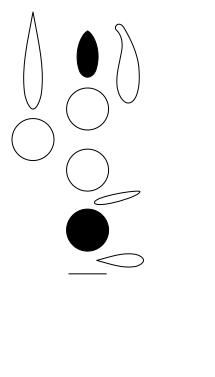

Upper Joint

William O. Smith - Epigrams, Movement II

Manipulation of the effective tube length.

Conclusion

This technique closes the bottom hole of the upper joint and creates more pitches to play. In addition, trills with right hand trill keys throughout this passage act similar to resonance fingerings on the full instruments in their slight timbral alterations. While playing sounds with the same fingerings as on the full instrument is easy, this specific technique is quite difficult. Understanding how to close the bottom of the upper joint (notated as the first tone hole on the lower joint) in an unforced manner is essential in reproducing this sound.

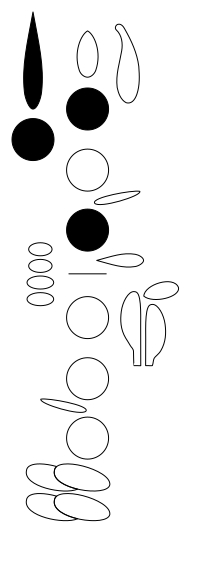

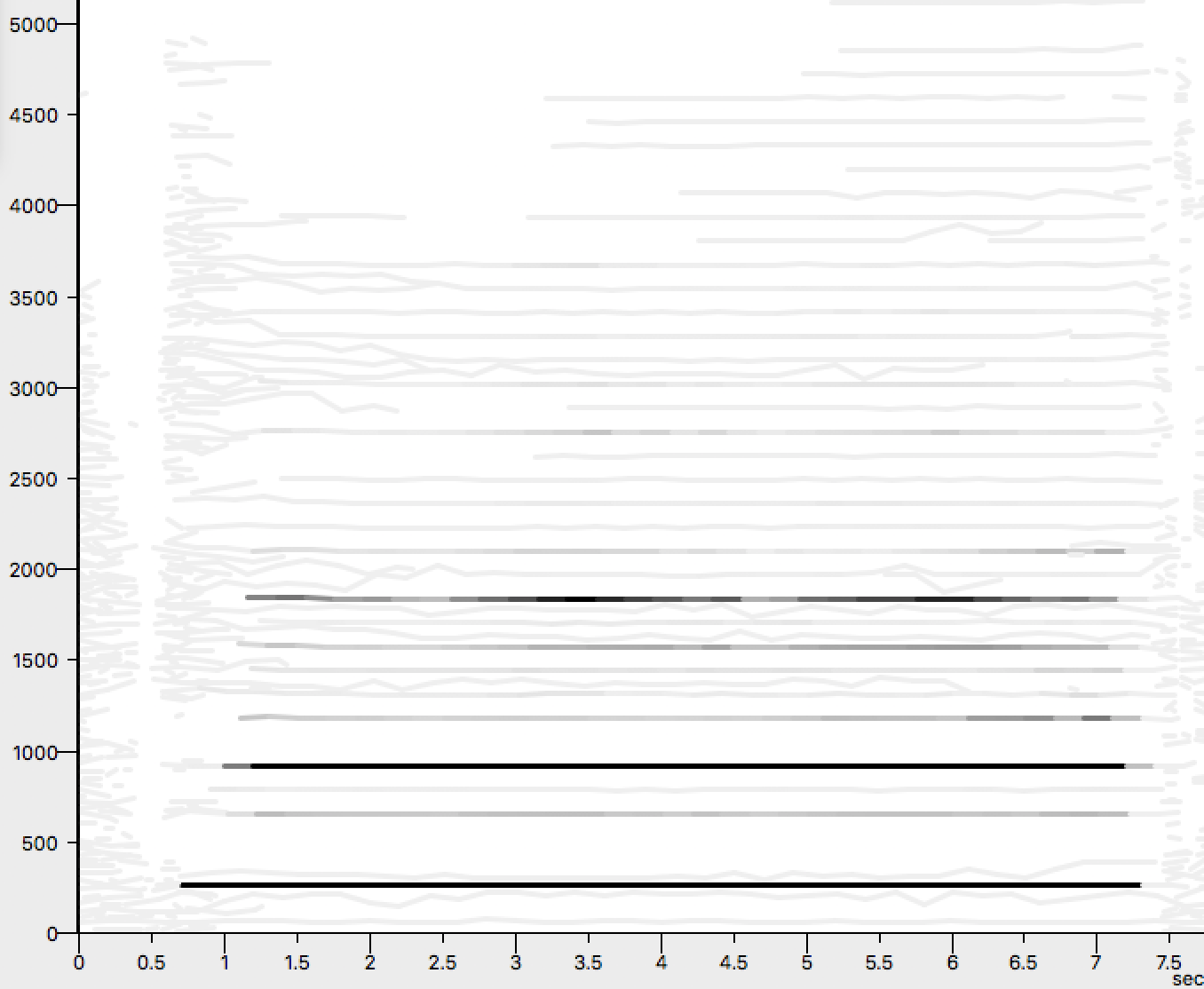

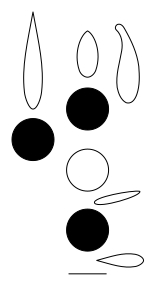

Lower Joint

William O. Smith - Epigrams, Movement IV

Manipulation of the effective tube length.

Conclusion

This extended technique is very different from the pitches you can create on the upper joint. While almost all chromatically stepwise on the upper joint, the lower joint has its own unique set of intervallic relationships due to major changes in the effective tube length in which the air/energy has to travel. This technique, two multiphonics of two sounding sonorities on the lower joint, is difficult to achieve as each requires a different tongue position.

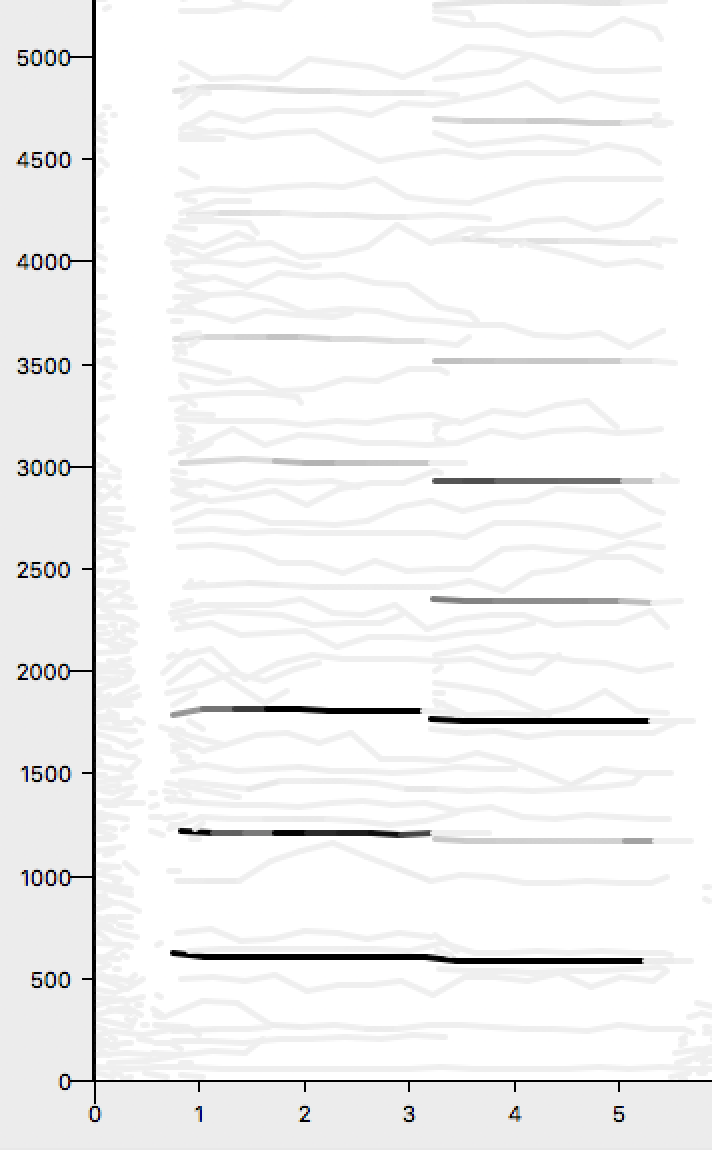

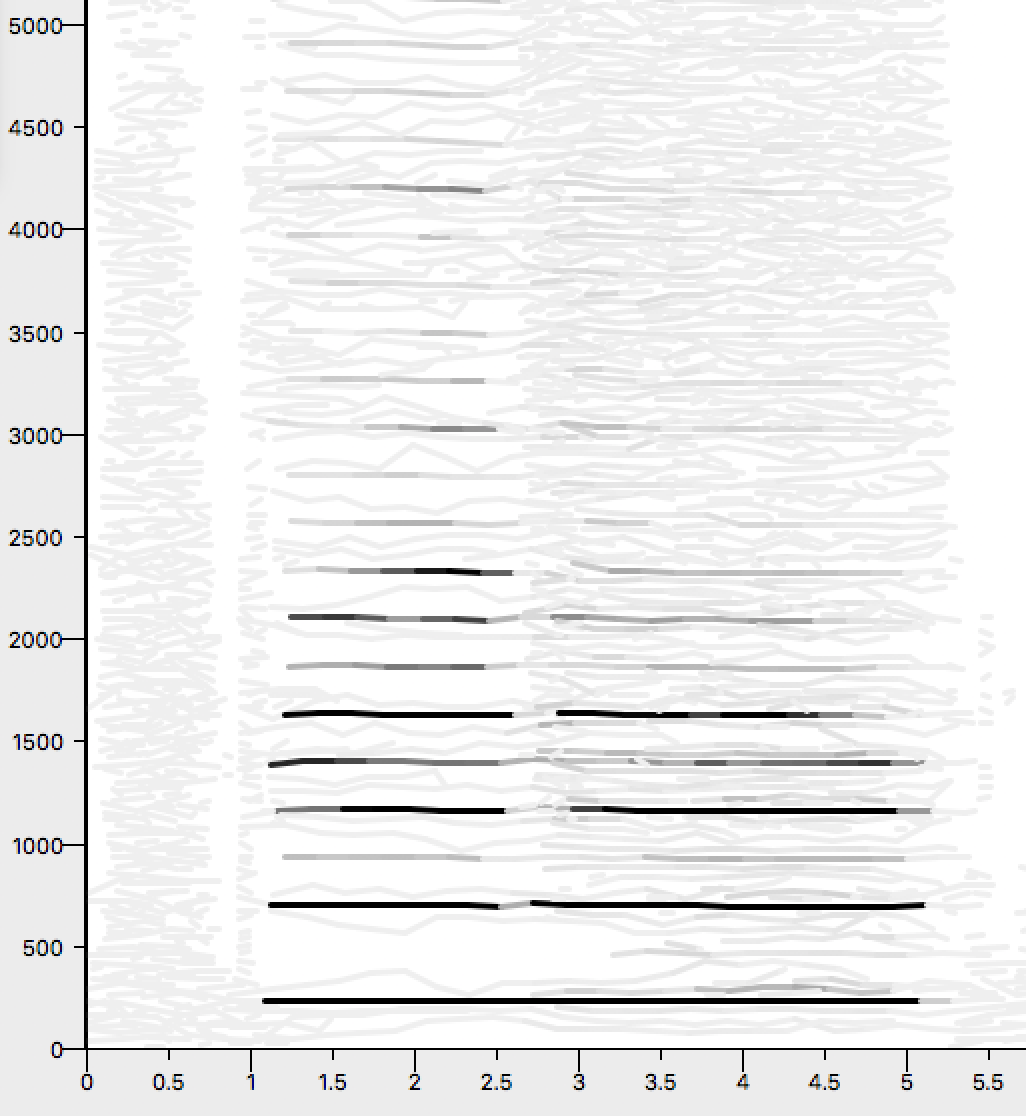

DemiClarinets/Double Clarinet

Conclusion

This exciting technique requires oral manipulation of a different nature. With two Bb clarinet mouthpieces needed to occupy where one mouthpiece typically resides, alterations to major parts of your oral cavity must occur. Instead of producing the correct air speed, voicing, and articulation for each respective note, you must compromise and find an oral cavity-based solution that works for both sounds. While there are multiple sonorities occurring at the same time, I wouldn’t call this a multiphonic as separate systems are creating individual pitches. This is difficult to say as they are both connected to the same energy and oral source. This specific excerpt notates for both instruments to play relatively the same pitches on both instruments at the same time. The spear graph shows the slight fundamental frequency discrepancies and the respective partial discrepancies due to variation in effective tube length for those fundamental pitches. With the addition of fingering coordination, this technique is difficult in general.